HISTORY

Psychiatric institutions have long carried both a negative stigma and mysterious aura. Because of their often remote, out-of-sight locations and portrayal as stark, dreary, and prison-like in films such as One Flew Over The Cuckoo’s Nest, these hospitals are often feared and avoided by the general public. From the outside, Dixmont was no different. For those who remember driving down Route 65 and seeing the menacing-looking boiler building and smokestack towering in the air, the often-used phrase “crazy house up on the hill” will probably also come to mind. They may also recall the rumors of unruly patients being chained up deep within it’s infamous underground tunnels. The hearsay only increased when the hospital shut it’s doors in 1984, with some even speculating that all of the patients were released to run free on the streets. However, what few will likely remember was the truth. Adding to the mystique of psychiatric institutions is the fact that most never set foot in one. Despite thousands driving past it’s outbuildings each day, the face of the hospital was intentionally invisible to the general public. So were its patients. The reality is that Dixmont’s history was actually rather uneventful. When it comes to state hospitals, that’s usually a good sign. However, it accordingly chronicles the progression of mental healthcare within a century, including the hits and misses.

Dixmont State Hospital was located on a wooded bluff overlooking the Ohio River. Peaking at a little over 1,000 patients, it was small compared to Western PA’s other major state hospitals. However, it was situated on 400 acres of immaculately-groomed property, making it perhaps the most picturesque hospital in the entire Pittsburgh area. For many, Dixmont was more than just a treatment center for mental illness - it was their home. Thus, it was designed and treated as such. The campus was like a small self-sufficient city, generating it’s own electricity and treating water/sewage. It had everything - a recreation center, manufacturing plant, farm, stables, greenhouses, picnic pavilions, trails through the woods, a cemetery, post office, train station, and a patient-run canteen. Of course, these were all common features of many mental hospitals at the time. However, what set Dixmont apart from others was it’s small but extremely dedicated and caring staff. Shown to the left is a mural painted by several artistic patients in appreciation for their favorite doctors and nurses. Art was a unique part of Dixmont’s rehabilitation philosophy. While many state hospitals across the country were facing lawsuits over patient abuse, neglect, and even murder, Dixmont’s administration and staff were doing their best to provide a tolerable and relaxing hospital experience despite decreasing state funds and limited resources.

In the 1850’s, the concept of psychiatric care was beginning to change drastically. Prior to then, those who were declared “insane”, “mad”, or “feeble-minded” by the public were sent away to be locked up in madhouses - jail-like facilities that were overcrowded, unsanitary, and often punitive in nature. At this time, there were few formal diagnoses of mental illness; one could be institutionalized for homosexuality, alcoholism, shyness, masturbation, disobedience, or just plain acting strange. It was essentially society’s way of dispensing with those who were disapproved of or seen as a nuisance. However, a young woman named Dorothea Dix would almost single-handedly change psychiatric care in the United States forever. A former school teacher forced to retire early due to sickness, she traveled to England in search of a cure. Upon arrival, she began to notice the superior quality of British healthcare and became interested in the ongoing movement of social reform, social welfare, and most notably, lunacy reform. She returned to the United States inspired by British progressive ideologies and began her crusade to reform American psychiatric care in her home state of Massachusetts by personally conducting a state-wide investigation of mental health facilities. The results were appalling - these facilities were completely unregulated and unfunded by the government, often run by charitable local individuals who faced the immense burden of caring for those who could not care for themselves. Despite an attempt at a good deed, these madhouses were far from righteous. Inhabitants were chained, malnourished, often unclothed, and beaten if they did not behave. Dix published her findings in a muckraking report titled Memorial to the Massachusetts State Legislature in 1843:

THE BEGINNINGS OF PSYCHIATRIC REFORM - DOROTHEA DIX & THOMAS STORY KIRKBRIDE

Gentlemen - I respectfully ask to present this Memorial, believing that the cause, which actuates to and sanctions so unusual a movement, presents no equivocal claim to public consideration and sympathy. Surrendering to calm and deep convictions of duty my habitual views of what is womanly and becoming, I proceed briefly to explain what has conducted me before you unsolicited and unsustained, trusting, while I do so, that the memorialist will be speedily forgotten in the memorial.

About two years since leisure afforded opportunity and duty prompted me to visit several prisons and almshouses in the vicinity of this metropolis. I found, near Boston, in the jails and asylums for the poor, a numerous class brought into unsuitable connection with criminals and the general mass of paupers...

...I proceed, Gentlemen, briefly to call your attention to the present state of Insane Persons confined within this Commonwealth, in cages, stalls, pens! Chained, naked, beaten with rods, and lashed into obedience.

“

”

The report struck a chord with the legislature and prompted the state to fund the expansion and reform of hospitals. However, her mission did not stop there. From the 1840’s to the 1880’s, she traveled to as many states as she could reach, devoting extraordinary effort into investigating each state’s hospitals, reporting the findings to legislature, and working on committees to draw up the proper appropriation bills to facilitate real and immediate change. Following the Civil War, she focused her efforts on reforming and rebuilding asylums in the devastated South.

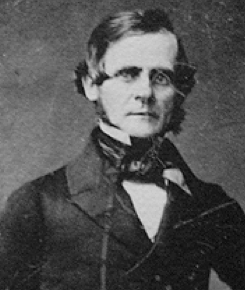

However, Dix was not alone in her cause. Thomas Story Kirkbride, a privately-practicing physician with a medical degree from University of Pennsylvania, unexpectedly fell into mental health reform much like Dix. At the age of 31, he received the opportunity to become superintendent of Pennsylvania Hospital for the Insane. Although he lacked any practicing experience with psychiatry, his internship experience and credentials were sufficient for the job and he accepted out of practicality. Upon taking the position, he began to imagine ideal mental illness treatment and how hospitals should be constructed in the future. In 1844, he founded the Association of Medical Superintendents of American Institutions for the Insane as a way to build the growing philosophy of moral treatment and spread it to other hospitals throughout the nation. This was eventually renamed the American Psychiatric Association, as it is known today. He is best known for creating the Kirkbride Plan, a set of standards by which psychiatric institutions could be built to best facilitate moral treatment. Kirkbride believed that asylums should live up to their name and provide unconditional asylum to those with mental illness rather than punish them for it. He also believed that the design of the building was just as important to the recovery of the patient as their treatment. Thus, he proposed that institutions should be built like castles with Victorian-era architecture and be spacious enough to allow for comfortable rehabilitation. “Kirkbride Buildings”, as they have come to be called, featured sweeping wings flanked behind the center of the building in a V-shape to provide patients with sunlight and fresh air, long and wide hallways, wards separated by gender and severity of illness, and construction of rock or brick to lessen the risk of fire. They were also situated on numerous acres of well-kept private land away from the hectic lifestyle of cities and often made use of patient-run farms. Hospitals were built according to the Kirkbride Plan all across the United States. In fact, many of them were so idyllic that wealthy families would use them as vacation spots when in need of relaxation. While some criticized his plan for prolonging the stays of patients and shifting attention away from the advancement of real therapy and rehabilitation methods, his philosophies of moral treatment and attention to detail changed the lives of institutionalized patients and is still revisited today when studying treatment of psychiatric patients.

In the 1850’s, Pittsburgh was in dire need of a dedicated mental institution. Although Western Pennsylvania Hospital had a psychiatric department, it was not sufficient and quickly became overcrowded. Dorothea Dix traveled to Pittsburgh to be part of the committee tasked with constructing the city’s first mental institution. Planners originally wanted it to be located in the thriving town of Homestead and even purchased the property for it’s construction, but a Kirkbride-influenced Dix disapproved, stating that it should be in a rural area to give patients privacy and plenty of open space. She instead chose the relatively-undeveloped Ohio River valley between Pittsburgh and Sewickley.

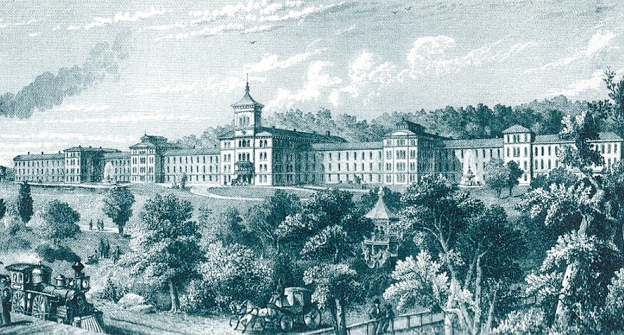

The committee was appropriated $10,000 to purchase 407 acres of farmland along the Ohio River. The hospital was designed by architect Joseph W. Kerr according to the Kirkbride Plan (Kerr’s original sketch is shown above), and construction began in 1859 starting with a grand ceremony in which a time capsule created by Dorothea Dix was placed in the cornerstone. The center administration section and two wards on either side were completed in 1862 and opened as Department of the Insane in the Western Pennsylvania Hospital of Pittsburgh. The main building would later be named Reed Hall after Dr. Joseph Allison Reed, the hospital’s first superintendent. Dix reportedly spent a few months living in the hospital to ensure it met all expectations. Originally, only 113 patients were transferred from Western Pennsylvania Hospital, but by the end of the 1800’s, the Kirkbride buildings’s wings had been extended and over 1,500 patients occupied the hospital. In 1907, the hospital separated from Western Pennsylvania Hospital and was renamed Dixmont Hospital for the Insane in honor of Dix. In 1921, the name would be again shortened to Dixmont Hospital in an effort to disuse the pejorative term “insane” in the mental health field.

Beginning in the late 1800’s, mental hospitals all over the world were facing the growing problem of overcrowding. With peaking populations, industrialization of cities, and large numbers of soldiers returning with PTSD, hospitals had to use every inch of excess space for patient housing. Dixmont was no exception. Hallways and attics were lined with temporary beds to support the enormous influx. At one point following World War I, the hospital maxed out at 1,700 patients and was forced to cease admissions. Dixmont, a then-private hospital with limited financial resources, was entering into an era of financial troubles that would last for the next five decades. During the Great Depression, the hospital was understaffed and could not even afford to pay most of its employees’ salaries, providing them only with room and board. The facilities were inadequate, obsolete, and in major need of repair, but budgets prohibited any progress. The situation became bad enough that the Pennsylvania Department of Welfare took ownership of the hospital in 1946, renaming it Dixmont State Hospital. With the added funding from the state bailout, Dixmont began to morph into a modern psychiatric institution and began a slow progression towards improvement.

However, the new era dispensed with Kirkbride’s hands-off approach and instead centered around the modern belief that mental illness could be cured biologically. The 1950’s saw the construction of several much-needed modern buildings including the Hutchinson Building, a medical-surgical building named after Dr. Henry Hutchinson, Dixmont’s superintendent from 1884 to 1954. At the time, medical/surgical buildings reflected the modern belief that mental illness could be treated biologically using new medicine and surgical procedures - just like physical illness. As such, they were constructed more like general hospitals where the average stay time of patients was measured in days or weeks rather than years. The mental health community was hopeful that patients could simply be brought to a medical/surgical facility, be administered a biological treatment, and be on their way before long - effectively eliminating the need for sprawling “human warehouse” institutions. While the intentions were good, many of the antipsychotic medications and procedures administered at these new facilities left patients repressed and unable to care for themselves. In the Hutchinson Building, lobotomies and electro-shock therapy took place each Monday and Thursday. While these inhumane therapies had limited success and were ultimately eliminated from regular use, antipsychotic medication began to dramatically improve by the 1960’s and ushered in the deinstitutionalization movement; the new philosophy that massive long-term institutions should be phased out in favor of less-isolated, community-based treatment centers such as group homes.

Deinstitutionalization refers to two major accomplishments in the field of mental health. The first was the redefinition of who is considered “insane” and, subsequently, the release of those who truly did not belong in mental hospitals. Really, this idea had existed long before the mid-20th century, but it reached it’s culmination in the 1960’s when John F. Kennedy passed the Community Mental Health Act. He gained a special interest in psychiatric care when his sister Rosemary received a failed lobotomy at the age of 23, leaving her unable to walk or speak. The specific point that gained public attention was the fact that she had no discernible mental illness aside from a lower-than-average IQ which led her doctors to believe that she was retarded. In addition to the President spearheading the effort, there was now a real solution that would allow huge number of patients to be released and restart their own lives in the real world. With the introduction of new drugs such as Thorazine, those with treatable mental illness could now live autonomous lives outside of hospitals. Populations in mental hospitals all across the country decreased.

Now that the high-functioning patients had all been released, it was becoming apparent that Kirkbride’s philosophy was now irrelevant. No longer was a stately building necessary to house long-term patients en masse. By the 1970’s, the only patients left at hospitals like Dixmont were those who had no family or were too poor to move out, as well as the elderly who had been admitted prior to the era of deinstitutionalization. However, these individuals were not lost on psychologists’ efforts to change mental health. Studies showed that by continuing to keep these patients locked up, they were learning to be dependent, helpless, and lethargic. In essence, the hospital was their disease. However, as seen in movies such as One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, Girl Interrupted, and Shawshank Redemption, moving out of an institution into the real world is not an easy task. In fact, it is one which many fear and avoid. Although the state wished to close Dixmont as soon as possible, the hospital launched an effort to keep itself open as long as possible in order to provide it’s lingering patients with a smooth transition. Although Dixmont’s administration continued to consider plans for expansion up until closure, the next two decades were not so much about growth, but merely making the best of what the hospital already had to work with.

In 1971, Dixmont finally opened a much-needed new facility: the Cammarata Building, a $2 million modern geriatric center for it’s aging population (shown to the left). The facility was spacious and incorporated generous use of natural lighting to provide patients with a more domestic environment. Also symbolic of deinstitutionalization was the building’s location - slightly off-campus and very close to Emsworth neighborhoods. This building was also the meeting place of the volunteer group, a collection of charitable individuals whom Dixmont relied on heavily during a time when it was badly understaffed. These volunteers conducted re-socialization classes in which patients could learn basic life skills such as writing, social etiquette, and taking care of themselves in preparation for their release from the institution. Below are a group of elderly women lining up for a photograph in the geriatric center.

In 1972, the state had announced that it planned to shut down Dixmont. However, public outcry from both employees and Pittsburgh residents delayed this. The Department of Welfare continued to lower it’s budget for state-run hospitals, leaving Dixmont in a continually worse financial situation year after year. Nonetheless, superintendent Dr. Robert Weimer kept an optimistic approach. Despite a tight budget, he developed a strategy to keep the hospital’s doors open. He was responsible for the hospital’s first-ever accreditation by the Joint Commission on Accreditation of Hospitals, an achievement which was earned through subtle and cost-effective methods to improve the hospital such as the removal of bars from the windows, naming of streets, decrease of the average patient stay time, demolition of unused buildings, and a strong volunteer group. Dixmont was the first and only state hospital in Western PA to achieve accreditation. Perhaps his most clever move was one which made the hospital hard to destroy: he got Reed Hall listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1981. Of course, these moves did not prevent the hospital’s inevitable closure, but only delayed it. However, all of the employees at Dixmont took the stance that the hospital should continue to operate as if it’s future is unlimited. In fact, records show that in the early 80’s, plans were being made to construct a new state-of-the-art activities center with a swimming pool, an education center, and a parking garage. However, these plans would never be completed. On Valentine’s Day in 1984, it was announced that all patients would be transferred to Mayview and Woodville State Hospitals over the next few months in preparation for it’s closing. On June 30th, 1984, Dixmont’s doors were locked for the last time.

After Dixmont closed, the state was now left with the task of deciding what to do with the property. Although offers from developers came in almost immediately after it’s closure, progress was slow due to the numerous obstacles presented by the atypical configuration of the property. One such problem was that different areas of the site were zoned residential, commercial, or industrial, all totaling 22 buildings of different sizes, ages, and uses. In addition, the buildings were all reliant on the power, water, and sewage treatment plants and did not have these utilities of their own. This led to debate over whether the buildings should be divided into individual parcels of land or if the site should be sold as a whole. Although the state had initially hoped for a developer to purchase it all, it became apparent that the Cammarata Building was the most desirable structure and would likely need to be sold individually. Another major turnoff for developers was the fact that the entire site would need an environmental cleanup before new construction could begin. This put an end to a bid from St. John’s Hospital, a proposal that came close to reusing nearly all of the buildings and converting them into senior citizen living. In 1984, the state allowed Holy Family Institute to freely use the Cammarata Building and gymnasium for two years after their facilities burned down nearby.

With all development plans looking grim, Dixmont’s abandonment was becoming a problem. Vandals, explorers, and the homeless were finding ways to break into the buildings. In fact, neighbors often reported people squatting in Reed Hall full-time. The site was also a growing fire hazard. Power to the fire alarm systems was cut, and with the pumping station shut down and stagnant water in the reservoir, only a handful of hydrants on the property were operational. Although their masonry and cement construction allowed the buildings to be relatively fire-proof, the fire marshal predicted that the site was a prime target for arsonists. In 1986, the state had to hire a security firm to monitor the property at all hours. However, this did not seem to stop trespassers, and perhaps more importantly, could not stop the forces of nature from invading the buildings.

When it was discovered that the basement of the boiler building was flooded with 4 feet of water only a few years after the hospital closed, the possibility of easily reusing the site as a self-sufficient campus was greatly weakened. As the years drew on, more windows were smashed, more buildings were flooded, and the property became massively overgrown. Soon, development plans began to move away from the idea of reuse and instead called for demolition. In 1989, the land was considered for the site of a new $50-million county jail. However, fierce opposition from local residents forced the developers to look elsewhere. No serious development offers would be made for the next ten years, and the campus continued to sit vacant.

On June 7th, 1995, the fire marshal’s prediction became true when an arsonist broke a glass window in the front door of Reed Hall and set fire in four different locations with the intent to burn the entire structure down. The security firm failed to report the intrusion. Drivers on Route 65 called 911 when smoke was seen rising up from the hill. Firefighters’ efforts were slowed by the lack of functional fire hydrants on the property and the poor condition of the roads. Despite this, the fire was eventually contained and didn’t spread to any of the building’s wings, but it completely destroyed the chapel, library, and 2 floors of the administration section. This left the once-grand facade of the building a hollowed-out shell. Soon after news of the fire got out, scrappers invaded the building and removed anything of value. Because Reed Hall’s windows were institutional models with a special blind-like design to prevent escape, scrappers took every window out of the building, allowing the interior to be exposed to the elements. Appraisals of the property fell drastically after this. In the late 1980’s, the asking price for Reed Hall alone was several million, but the price for the entire property was reduced to approximately $700,000 by the late 90’s due to the destruction.

In 1999, there was new hope for the site when Ralph Stroyne, a Kilbuck construction contractor and farm owner, purchased the entire 407-acre property for $757,000. Interestingly, the property taxes for the surrounding area dipped significantly following the sale. Renovation and abatement of the Cammarata Building began soon after the purchase and was later leased to the Glen Montessori School, the Verland Foundation, and as private office and warehouse space. He also planned on renovating the Hutchinson Building for use as his real estate office, but a flooded basement made the building worthless. Despite being on the National Register of Historic Places, Reed Hall was deemed beyond all repair and was slated for demolition. In 2002, Stroyne sold a portion of the property to ASC, a development firm known for it’s construction of Wal-Mart’s. Soon after lingering red tape was settled in court, plans were set into motion to develop the front 200 acres into a shopping plaza with a Wal-Mart supercenter and Applebee’s, and the back 100 acres into a residential neighborhood. The plan was met with mixed public opinion; residents welcomed the boost to the local economy that it would provide, but many protested the increased traffic and environmental pollution that would be created as a result. Local grocery stores also feared that a Wal-Mart in the area would put them out of business. Nonetheless, the project continued. In January of 2006, Dixmont met the wrecking ball. First, all asbestos was removed, costing as much as the property was originally purchased for. Demolition crews then worked from the bottom up, destroying the utility buildings and Hutchinson Building first, then chopping up Reed Hall from the right to left over a period of several days. The Dietary Building was the last building to go, finally ending with the implosion of the smokestack a few weeks after the property had been reduced to dirt. All trees, roads, and grass were removed. The only areas kept were the sewage plant in the event that Kilbuck Township may eventually incorporate it into it’s system, and the cemetery which was kept under state ownership by law.

THE CONSTRUCTION OF DIXMONT

OVERCROWDING AND DIFFICULT TIMES

1984-2006: ABANDONMENT & DEMOLITION

2006-PRESENT: ARRESTED DEVELOPMENT

On September 19, 2006, while crews were working to build up the land in preparation for the new shopping center, a catastrophic landslide occurred, spilling nearly 500,000 cubic yards of the hillside onto Ohio River Boulevard. No one was injured, but the highway was closed for weeks while cleanup took place and was reduced to two lanes for a long time afterwards as the land continued to inch downwards. In the months following the event, Wal-Mart announced that they were canceling construction of the store due to the unstable land. Instead, Wal-Mart brought in crews to gradually stabilize the land, a process that is still yet to be finished. Although rumors began to spread that Wal-Mart hadn’t given up on the site yet and may be planning a smaller development, a 2012 article in the Post-Gazette reported that a company spokesman declared the development dead and confirmed plans to plant 7,000 trees and turn the property into a gently-sloping meadow. The article also revealed that crews were nearing the end of the major stabilization and ready to begin reforestation, but that the site will require long-term monitoring and that it could be years, if not decades, before anything can be built. Wal-Mart and it’s developers are still wrapped up in civil lawsuits over which party caused the slide and who is responsible for stabilization, but locals have praised the frequently-chided company for it’s diligent and continued efforts in remedying the situation. Kilbuck officials are still optimistic about seeing new development on the site sometime in the future, but would also be pleased with just having a public park.

1859 - Construction begins on the new Department of the Insane in the Western Pennsylvania Hospital of Pittsburgh facility. A groundbreaking ceremony is held.

1862 - Construction is completed and hospital opens at full capacity with 140 patients. Dr. Joseph Allison Reed is the first superintendent.

1867 - An addition is built on the west wing of the hospital to accommodate the rapidly-increasing patient population.

1870 - An addition is built on the east wing of the hospital; the building now has a capacity of 400 patients.

1878 - Original laundry building is constructed, later to be used as the gym/maintenance shop.

1884 - Dr. Reed passes away. Dr. Henry Hutchinson becomes superintendent and would continue to be until 1945.

1889 - The 162-bed Men’s Annex building is constructed.

1891 - Patient population is at 733.

1899 - Patient population is at 1,035.

1907 - Hospital separates from Western Pennsylvania Hospital and is renamed Dixmont Hospital for the Insane in honor of Dorothea Dix. A new tuberculosis building is opened.

1910 - The Dietary Building is constructed.

1911 - Patient population is at 1,004, 250 of whom are sleeping on the floor.

1918 - World War I ends, sending thousands of soldiers home with what is now known as Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder. Dixmont's overcrowding worsens.

1921 - Name is shortened to Dixmont Hospital.

1929 - Great Depression begins. Dixmont suffers financially through the 1930's.

1933 - Industrial Arts building is constructed.

1945 - Dixmont is taken over by the PA Department of Welfare and is renamed DIxmont State Hospital. Dr. Leonard Rosenzweig becomes superintendent.

1946 - Dr. Joseph Cammarata replaces Dr. Rosenzweig and attempts to rectify the hospital’s poor facilities and shortage of employees.

1947 - Patient population is at 973.

1949 - Construction begins on the new admissions/medical building, but a landslide delays the project. Men’s Annex is substantially renovated.

1953 - New boiler building/power plant opens.

1954 - New Admissions and Treatment Building is completed and would later be named after Dr. Henry Hutchinson, the long-time superintendent who passed away in 1947 at the age of 92.

1955 - New laundry building is constructed.

1965 - Patient population is at 932. Men’s Annex building is closed and condemned.

1966 - Superintendent Dr. Robert Weimer replaces Dr. Cammarata and modernizes the hospital by demolishing old vacant buildings, removing bars from the windows, unlocking many patient rooms, and improving the grounds. The period while he was superintendent was often called “Dixmont’s Renaissance”.

1967 - The hospital is accredited for the first time by the Joint Commission on Accreditation of Hospitals.

1969 - After 5 years of stalled progress due to concerns over the stability of the land, construction begins on the new geriatric center.

1971 - New geriatric center opens and would later be named after former superintendent Dr. Cammarata, who passed away in 1975. Renovations are under way in the hospital's other buildings. The Nurses’ Dormitory closes and the first floor is reused as the Dixieland Canteen.

1972 - The state proposes to close Dixmont, but it remains open after much public dissent. The state recommends a moratorium on new construction for all state hospitals. Meanwhile, Dr. Weimer establishes the hospital’s first deaf unit.

1973 - Patient labor is discontinued following new legislation.

1975 - Patient population is at 454.

1977 - After being cited by the EPA, the boiler building is renovated and converted from coal to oil-burning.

1979 - A public donation campaign allows the Hutchinson Building to be air conditioned. Dr. Weimer retires and is replaced by Dr. Karl Ludwig, who would quit two years later. Patient population is at 356, 443 staff members are employed, and the hospital is praised for its major improvements over the past decade.

1981 - Reed Hall is listed on the National Register of Historic Places. Dr. Wendell Hunt becomes the hospital’s last superintendent.

1983 - Patient population is at 177 - all but 50 patients are living in the Cammarata Building. Dixmont downsizes by closing the top two floors of Reed Hall and demolishing the abandoned Nurses' Dormitory.

1984 - Dixmont’s closure is announced on Valentine’s Day and the hospital closes on June 30th.

1986 - Holy Family Institute continues to occupy the Cammarata Building.

1989 - The county plans to demolish Dixmont's buildings and construct a county jail on the former campus, but the plan faces local opposition and is scrapped.

1995 - An arsonist sets fire to Reed Hall, destroying the upper two floors of the center administration section.

1999 - Ralph Stroyne purchases the Dixmont campus. The Cammarata Building is renovated, excess trees and overgrowth is removed, and scrap metal is salvaged from the buildings.

2002 - Most of the property is sold to a development firm with the intention of building the River Pointe Plaza, a shopping center anchored by a Wal-Mart and Applebee's.

2006 - The remaining buildings at Dixmont are demolished. Later that year, a massive landslide from the property spills onto Ohio River Boulevard.

2007 - Wal-Mart cancels construction and begins to restabilize the land.

2012 - Stabilization of the site nears completion and developers reaffirm that no construction can take place on the site for several years.

TIMELINE

Dr. Thomas Story Kirkbride

Dorothea Dix

Reed Hall, Entrance

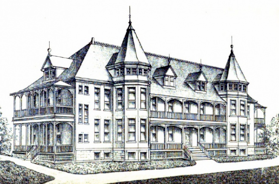

Men’s Annex Building

Reed Hall, Patient Ward

Reed Hall, Beds in the Attic

Hutchinson Building

Dr. Joseph A. Reed

1818-1884

Tenure: 1862-1884

Dr. Reed approached his position with progressive ideas and a compassionate, familial sprit. He and his family resided on the fourth floor of his namesake building and would dine with the patients nightly. Under his tenure, he immaculately decorated the wards and would often host lavish dances and dinners. He reportedly would only hire staff who showed an equal sense of kindness. He enforced humane treatment throughout the hospital through measures such as forbidding the use of restraints and talking down to patients.

Dr. Henry Hutchinson

1855-1947

Tenure: 1884-1945

Beginning as an eccentric and prodigious young assistant physician at Dixmont in 1879, Dr. Hutchinson took position as superintendent at age 29 and continued as such until age 90. Throughout his extensive career, he concerned himself with every detail of the hospital, from patients’ personal lives to the well-being of his employees. He was known for riding across the campus everyday in a horse-drawn carriage and taking notes of anything that could be improved. He later married Dr. Reed’s daughter and was given the honorary position of “Superintendent Emeritus” until his death in 1947.

Dr. Joseph A. Cammarata

1902-1975

Tenure: 1946-1966

Dr. Cammarata carried the hospital through a rough time in its history. He was tasked with cleaning up an outdated institution, making the most of an underfunded state budget, and having to answer to the public for Dixmont’s neglect. His job was often a thankless one, but he refused to let the state compromise the quality of the hospital and laid the groundwork for projects that would eventually renew the hospital’s reputation. His open door policy went a long way in keeping good morale among the patients and staff.

Dr. Robert E. Weimer

1917-1998

Tenure: 1966-1979

Dr. Weimer ushered in what was described as a “Renaissance era” for Dixmont. A believer in humanistic psychology and a patron of the arts, he brought modern and innovative new therapy techniques to the hospital and overhauled the campus into one of the best in the state through simple and effective changes that gave patients more freedom, beautified the campus, and got the community involved through regular festivals and events. His work earned Dixmont the state’s first and only JCAHO psychiatric accreditation.

DIXMONT’S INFLUENTIAL SUPERINTENDENTS

® Copyright 2014 DixmontHospital.com, All Media Fair Use